Concurrent Trademark Use: Can the Domain Name System Accommodate?

Rob Kalinsky

April 16, 1999

Cyberspace Law Seminar

Table of Contents

Network Solutions, Inc. (NSI) Current Dispute Policy

Other's Solutions to the Problem

With every passing day, more businesses are taking advantage of the Internet as a vehicle to reach consumers. To operate a web site on the Internet, a business must choose a domain name, such as

www.ibm.com, which functions as the address for the site. A logical choice which a business may choose when selecting a domain name is to utilize its trademark as its domain name.There is no problem with this arrangement until it is recognized that current trademark law allows multiple businesses in different lines of work to use an identical trademark as long as it is unlikely that there would be confusion. The web, however, because of its universal structure, allows only one of the businesses to utilize its trademark as its domain name. This means that the other concurrent trademark owners are left choosing less advantageous alternatives.

This paper will consider the traditional trademark law that allows concurrent trademark use and the problems this creates when applied to the Internet. A survey of proposed solutions to this problem will be provided, and each solution will be examined to determine its strengths and weaknesses. Finally, a solution will be presented that would help to alleviate the problem in the most advantageous manner for all parties involved.

Trademark law is a branch of intellectual property law that deals with rights which may exist in words, symbols, or other devices that identify the goods or services of a business. The first user of a trademark has rights to the mark.

[1] The rights associated with a trademark are codified in the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051-1127 (1994).Typically, once a business has established a trademark, this precludes others from using an identical trademark or one close to it. However, trademark law allows for concurrent registration

[2] of identical trademarks where the second trademark owner is in a sufficiently different line of work such that confusion between the two businesses and their marks would be unlikely.[3] [4] like McDonalds or IBM are not available for concurrent use, many trademarks today can be used concurrently. For example, the trademark ACME has been officially registered more than sixty times.[5] This allows businesses in different lines of work to enjoy the ACME trademark without creating confusion for the consumer. For example, there could be both an ACME Computer Company and an ACME Bakery that could function with the same ACME trademark without creating confusion.A domain name functions on the Internet much like a street address functions to locate a business or home. The domain name provides a reference that is easily remembered by an individual who wishes to visit a specific web site. A person is able to enter a domain name, such as www.acme.com,

[6] into a web browser which then queries a domain name server (DNS). The domain name is resolved by the DNS into an Internet Protocol (IP) address,[7] such as 128.255.56.02, which is then used to locate and retrieve the desired web page. Therefore, the use of domain names is not necessary for the web to function (IP addresses could be used directly), but domain names are much easier than IP addresses for humans to remember and use.The domain name is actually part of a uniform resource locator (URL), which would be stated as http://www.acme.com. The "http://" portion of the URL indicates to the computer that HyperText Transport Protocol

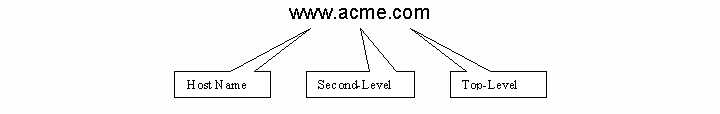

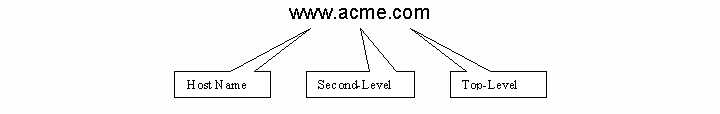

[8] will be used to download the web page. The domain name consists solely of www.acme.com. The anatomy of a domain name can be broken into the three components that are shown in Figure 1.[9]

Figure 1 - Anatomy of a Domain Name

The top-level domain name, ".com," loosely describes the purpose of the organization associated with the domain name. The .COM top-level domain was created to designate business or commercial web sites. Other top-level domain names include .NET and .ORG, which are also administered by Network Solutions, Inc. (NSI),

[10] and .MIL, .GOV, and .EDU, which are administered by the government. In addition, there are country-specific top-level domain names such as .jp (Japan), .uk (United Kingdom), and .us (United States) which are administered by organizations within each country.The second-level domain name, "acme," describes the owner of the web site. Businesses tend to use an intuitive name as their second-level domain, with a natural choice being to use their trademark. Registration for second-level domain names is performed by the administrators of the top-level domain name desired. Finally, the host name, "www," indicates the specific computer on an organization's network which provides the web site services. Most frequently, this computer is designated with the familiar "www."

A business will typically register its second-level domain name under the appropriate top-level domain, which is .COM for commercial entities. While the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA)

[11] has overall authority for the top-level domain names, it has assigned authority over to the Internet Network Information Center (InterNIC).[12] The InterNIC, in turn, has contracted with NSI[13] for processing domain name applications. Therefore, a business or other entity interested in registering a second-level domain name would submit an application to NSI.A domain name is global in performance, so that it will function over the entire Internet, regardless of geographic location of the user or the web site server. The Internet is designed so that geographic distances are transparent to the end user. For example, a person entering the URL http://www.acme.com in China will be directed to the same web site as a person entering the same URL in Maine.

How do trademarks and domain names work together?

Normally when a business wishes to create a presence on the web, it will register a second-level domain name that has meaning to its customers. As indicated previously, a natural choice for a business would be to register its trademark as its domain name. A domain name can be thought of as a street address, indicating the location of a web site on the Internet.

[14] However, in the context of business web sites, the domain name can come to resemble an identifier of services and goods offered by the business at a web site.[15]While it is true that a domain name in itself is used simply to make human access to web sites on the Internet easier,

[16] use of trademarks as domain names by businesses to promote and sell products and services on the web[17] could and is increasingly recognized as the use of a trademark which is governed by intellectual property law. The domain name in this context becomes more than an address, functioning as an identifier for the goods and services of the business located at that web site.The use of a business' trademark as its domain name normally creates no problems. However, when examined in light of concurrent trademark use, conflict results when two concurrent users of the same trademark both wish to use the trademark as their domain name. While trademark law allows this concurrent use,

[18] it has been indicated that the web's universal nature allows only one business to utilize the specific trademark as its domain name. Several commentators who have examined this problem have drawn an analogy to the problem created by alphanumeric 800 numbers, where several companies may wish to have vanity numbers spelling out the same catchy name.[19]It is important to distinguish the problem of concurrent trademark use as applied to domain names from other problems associated with domain names on the Internet, such as infringement or cybersquatting. Infringement

[20] deals with cases where a second party accuses a first party of wrongfully using the second party's trademark as the first party's domain name. This can most easily be seen in the case of a famous trademark,[21] because any use of a famous trademark by a third party can lead to dilution of the mark. Cybersquatting is similar to infringement, in that the party using the trademark as their domain name is infringing on the rightful use by the trademark owner.[22] However, a cybersquatter is identified as a person who has no real intention of using the domain name for him or herself, but has registered the domain name using the trademark of the business for the purpose of selling it to the business at a profit.Neither infringement nor cybersquatting issues are not problems that are unique to the domain name system, and both can be handled using existing trademark law.

[23] Conversely, concurrent trademark use as applied to the domain name system presents a novel problem which trademark law and domain name policy do not adequately address.Although the courts have not addressed the specific issue of concurrent trademarks and domain names, several illustrations of the problem have developed in the past several years, and it is anticipated that the problem will continue to grow as the web becomes more popular as a commercial vehicle. One example of this type of problem is the domain name

www.frys.com. Originally, David Peter registered the domain name www.frys.com to be used to promote his vending machine business, Frenchy Frys.[24]Subsequently California giant Fry's Electronics, Inc.,

[25] an electronics retailer, sought to stop Peters from using the trademark Frys as Frenchy Fry's domain name. Peters argued that there was no trademark infringement because the two businesses were in sufficiently different lines of business and no likelihood of confusion would result from Frenchy Fry's use of the domain name.[26] The dispute ended in court with a default judgment on other grounds in favor of Fry's Electronics.[27] This is one example where a large business with greater resources is able to exert its power to enjoin a smaller business, which has a legitimate claim to a trademark, from using its trademark as its domain name.Another example of concurrent trademark users vying for the same domain name is the case of the domain name

www.pabst.com. In 1996, Mike Pabst, owner of the advertising company Pabst Creative Communications, decided to create a presence on the web at www.pabst.com to promote his business. Several months later Pabst received a letter from Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, claiming that use of the domain was diluting the famous beer's trademark.[28] The much bigger Pabst Blue Ribbon was able to exert pressure to get NSI to put the name put on hold status, thereby freezing the domain name and forcing Pabst Creative Communications to choose a different one.These two examples illustrate the problems that can arise when two concurrent trademark users both wish use their trademark as their domain name. As these cases indicate, typically the larger business is able to exert pressure until it can either enjoin the smaller business from using the domain name or even secure use of the domain name for itself. However, it does not seem to be satisfactory in a system that allows more that one business to use an identical trademark to recognize only the largest user of the trademark for domain name purposes. Each business should be able to choose a logical domain name for its presence on the web, and normally this choice would be its trademark.

An overview of proposed solutions to this problem will be examined below. First, the current NSI policy for domain name disputes will be addressed.

[29] Next, proposed solutions to the problem will be examined, and the strengths and weaknesses of each explored. Finally, a novel solution will be proposed, attempting to maximize benefits to both trademark owners and end users. These solutions will be examined in a national context and will not address the larger global concerns that are acknowledged. In addition, all analysis will be done under the assumption that both parties have legitimate claims to the use of the trademark as a domain name.Network Solutions, Inc. (NSI) Current Dispute Policy

A cursory reading of the current NSI Dispute Policy

[30] will illustrate that NSI has taken a passive approach to the problem of trademark use as domain names. NSI notes that it is not equipped to determine if domain name use infringes upon a third party's trademark rights.[31] NSI makes it clear that it will neither act as arbiter nor provide resolution for disputes. Domain names are registered on a first-come, first-served basis, with no formal determination if a registered domain name may infringe on another party's trademark.A business which believes that another party's domain name infringes on its trademark rights must initiate Section 8 of NSI's Dispute Policy by providing NSI with an original, certified copy of trademark registration. If the trademark is identical to the domain name in question (i.e., the trademark matches the second-level domain name exactly without the "www" or .COM, .ORG, or .NET

[32]) NSI will compare the creation date of the trademark to the creation date of the domain name. If the domain name predates the trademark, NSI will take no action.However, if the trademark registration precedes the domain name, NSI will require proof of trademark registration from the domain name owner. If the domain name owner can provide adequate proof of trademark registration, NSI will take no further action. However, if the domain name owner cannot provide adequate proof, NSI will either assist the owner in choosing a different domain name or place the disputed domain name on hold status. The hold status means effectively that the domain name is not available for use by any party. The domain name will remain in hold status until the dispute is resolved through such avenues as litigation or arbitration.

There are several apparent problems with the current domain name dispute policy as applied to concurrent trademark usage. First, while it may be proper for NSI to distance itself from any determination of trademark rights, its policy only recognizes registered trademarks

[33] and provides no recourse for holders of common law[34] trademarks.[35] Second, the policy fails to recognize the existence of concurrent trademarks or how to deal with them. Third, the policy provides no direction for efficient resolution of disputes between trademark owners, leaving the most likely recourse to be costly litigation.The overall effect of the NSI Dispute Policy is to push the determination of which party should receive the domain name from NSI to an outside decision maker. This mechanism favors large trademark owners, who have the money and personnel to fight in court for a domain name. As is illustrated by the examples above, the resolution of a dispute under the NSI policy often ends with the smaller trademark owner surrendering the domain name to the larger owner, forcing the smaller owner to pick a less advantageous alternative.

Other's Solutions to the Problem

While there is no case law directed to resolution of concurrent trademark use as applied to domain names, there have been many proposals by Internet organizations and other knowledgeable persons to help solve or alleviate the problem. These proposals fall into four general categories: (i) maintain the status quo, (ii) replace the current domain name system, (iii) modify the current domain name system, and (iv) increase the number of top-level domains. Each strategy has benefits and weaknesses, and an overall examination of the proposals could result in a person concluding that none of them completely and adequately address the problems for both business owners as well as end users associated with concurrent trademark use on the Internet.

When examining the proposals, several general goals may aid analysis. It is important to look at each proposal from the perspective of both the trademark owner, who wishes to create a domain name based on her trademark, as well as the end user, who wishes to visit a certain business' web site. First, it appears that the optimum solution would be to allow every business to utilize its trademark as its domain name if it so desires. Second, proposals should provide mechanisms to resolve disputes between the trademark owners who are vying for the same domain name in an efficient and satisfactory manner. This would probably mean providing alternatives to costly litigation as well as limiting the dilution of both parties' trademarks.

Third, the resolution should create the least amount of confusion to the end user as possible. One aspect of this has been termed "guessability,"

[36] which encompasses the idea that the end user should be able to intuitively determine the domain name of a business or other entity on the web without becoming confused about which company is providing the services or goods on a web site. It is a distinct advantage to a business if its domain name is easily guessable by end users seeking to find the business' presence on the web. The most obvious guess for the domain name of a business would probably be its trademark.One of the obvious courses of actions is to leave the domain name system as it stands. This course of inaction has several flaws that have already been discussed, including the failure to provide resolution for trademark disputes, the failure to recognize common law trademark owner's rights, and the unfair advantages given to the larger trademark owners. Another problem with this proposal is that it would make the domain name for a certain business harder to guess by the end user.

[37] This is the case because only one of the concurrent trademark owners could use its trademark as a domain name, and the others would have to use alternatives that would be harder to guess. Although this would probably be the easiest solution in NSI's view, it does nothing to alleviate the inherent problems of concurrent trademark use on the Internet.Replace the Domain Name System

The next most obvious solution would be to scrap the domain name system as it now stands and replace it with an alternative system. One proposal in this category calls for the replacement of the domain name system with meaningless top-level domains

[38] with the requirement that each domain cannot have meaning in any language.[39] Presumably this would mean that when a business registered with NSI, NSI would generate a gibberish domain name for the business' use.There are several apparent problems with this proposal. Most importantly, creating gibberish domain names defeats the primary purpose of domain names, which is to create an easily remembered address for a web site. If gibberish domain names are to be used, one must question why the domain name system is used at all. Second, this system would not solve problems of confusion that end users may experience regarding the determination of which business was providing services or goods on a particular web site. Third, this proposal would completely eliminate any possibility of guessability. An end user would either need to know the domain name or would need to use other methods such as directories or search engines to find the business' web site. This proposal is not likely to be very attractive to a business that wants to reach a large audience based on its trademark.

A second proposal would be to retire the international top-level domain names (e.g., .COM, .ORG, and .NET) and rely solely on country specific top-level domains

[40] (e.g., .us for United States). The advantages of this proposal would be to limit disputes to a specific country, which would provide a clearer indication of where a lawsuit could be brought.[41] However, it is not apparent that this would provide any relief for concurrent use of a trademark within a certain country, and it would require that the end user know with which country a certain business is associated in order to be able to guess its domain name. In addition, multinational companies would undoubtedly wish to register domains in at least every country in which they provide goods or services, thereby creating problems for them as well as confusion for the end user.A third proposal would call for the elimination of the domain name system in favor of using IP address

[42] (e.g., 128.255.126.56). Analysis of this proposal would be similar to that for the gibberish domain names. Obviously there is nothing intuitive in an IP address and no possibility of guessability. Also, there is likely to be confusion for the end user who would be required to remember and enter a long string of numbers to obtain a particular business' web site.It is apparent from the three proposals that replacement of the domain name system would result in less guessability and greater confusion for the end user. Also, a business would not receive what it may desire, which is a presence on the web at the domain which corresponds to its trademark.

A third category of proposals would modify the domain name system as it now stands. The Internet International Ad Hoc Committee's (IAHC)

[43] proposal, in addition to adding new top-level domains as discussed in the next section, would require all applications for domain names be made publicly available on the web to allow trademark owners to monitor for infringement. In addition, the proposal would call for each domain name applicant to agree to participate in on-line arbitration as part of the registration process in the event of a dispute.[44] While this proposal would help to protect trademark owners and allow for more efficient dispute resolution, it does not specifically address the problems associated with concurrent trademark use and domain names.A second proposal in this category would call for the addition of information to each domain name. Some propose the addition of trademark classification codes that represent different fields of goods or services.

[45] This would result in such domain names as www.acme.9.com (class 9 is for computers). Others would add categories to the domain name from a list of controlled vocabulary,[46] and still others would add a personal string to domain names to distinguish personal web sites from business sites.[47] InterNIC also proposes requiring each domain name to contain a one-word description of the applicant's business, such as www.acme-grocery.com and www.acme-hardware.com.[48]All of these proposals implement the logic that a more distinct domain name would help to alleviate the problem of concurrent trademark use. However, cases can be imagined where an end user would not be able to intuitively determine which descriptor to add to a trademark to obtain a desired web address, thereby reducing guessability. Also, it is doubtful that this procedure could create meaningful, distinct domain names for the over sixty businesses registered in the United States with the ACME trademark.

A third proposal entailing modification of the system would be to require each domain name to include geographic data.

[49] This would result in a domain name such as www.acme.iowa-city.ia.us, which is a system currently used for most educational domain names. While this would help to distinguish domains, it would have the obvious problem of defining where a business is truly located, and it also does not solve the problem which arises when two concurrent trademark users are located in the same geographic area. Also, it reduces guessability by the end user, requiring knowledge of the location of a business, and it seems to frustrate the Internet's inherent non-geographic nature.Increase the Number of Top-Level Domains

The final category of proposals is really a subset of the previous section calling for modification of the domain name system, but it is worthy of separate analysis. Many commentators have proposed an increase in the number of international top-level domain names to alleviate the current congestion in the .COM, .NET, and .ORG domains. Some would create several new domains,

[50] and one even proposes to allow a business to use any name it chooses for a top-level domain, unconstrained.[51] All of these proposals contain the same basic problem in that as the number of top-level domain names increase, the harder and more confusing it becomes for the end user. In addition, the solution does not really address the problems associated with concurrent trademark use. Once again, it is likely that large businesses would register their trademark as a domain name in several different top-level domains.The substantive difference between these proposals calling for more top-level domains lies in who would regulate and register the new top-level domains. One proposal calls for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

[52] to step in and take over registration of top-level domains.[53] Others call for alternative sources to register the new international top-level domains. Two such organizations that already exist and register alternative top-level domain names are the ALTERNIC[54] and eDNS[55]. While these new top-level domains do relieve congestion, they still do not adequately meet the needs of concurrent trademark users. They may actually create burdens for trademark owners concerned with policing domain names to assure that none infringes on the trademark owner's rights.[56] Also, the possibility for end user guessability is again compromised as more and more similar top-level domains are created.This paper's proposed solution to the problem is similar to one given in an INTA bulletin, calling for a directory that would contain information about each domain name owner and provide links to the owner's separate web site.

[57] This proposal differs from the INTA proposal in that it does not call for a master directory, but it does provide links to each trademark owner's web site. The proposal is tailored to maximize benefits for both trademark owners and end users.The proposal calls for creation of what is termed a "linking page" when two or more concurrent trademark owners wish to use their trademark as a domain name. This linking page, which would be located at www.trademark.com (where trademark would be the actual trademark name in question), would consist of the following specifications as given in Table 1.

Table 1 - Linking Page Specification

|

Part |

Dimension |

|

Single Image |

100 pixels by 100 pixels, jpeg format, less than 25 kilobytes in size |

|

50 Words |

12 point Courier font, single-spaced |

|

One Hypertext Link |

12 point Courier font |

The image would probably be a company logo or other picture that would help identify the owner of the trademark. The text could be used in any way that the business wished, but it is anticipated that the text would be used to describe the business. Finally, the hypertext link would provide access to the trademark owner's actual, unregulated web site at a different domain name address. A sample linking page for owners of the ACME trademark is seen in Figure 2. An html version of the sample linking page can be seen by clicking

here.Figure 2 - Sample Linking Page

The linking page would be randomly generated each time the linking page is visited, so that each trademark owner's information would have an equal chance of being listed in the first, last, or middle positions of the linking page. The entity in charge of registration of the top-level domain would administer the linking page because this body would be in the best position to determine if two trademark owners have attempted to register the same domain name and wish to have a linking page created. The proposal would recognize both registered and common law trademark rights. If disputes arose as to trademark ownership or for other reasons, resolution would be handled via the mandatory arbitration clause that must be agreed to during domain name registration.

A scenario that illustrates how the proposal would work can be perceived by imagining registered trademark owner X who uses his trademark as his domain name. A second concurrent common law trademark owner Y wishes to create a presence on the web and attempts to register her identical trademark as a domain name. The registration entity notifies Y of the conflict with X, and X produces verification of X's registered trademark. Y cannot produce registered evidence because her mark is a common law trademark, so there are several options to consider. X could accept the validity of Y's mark, or X could challenge the validity of the mark via the arbitration clause. If the validity of Y's mark is established, the registering entity can create the linking page based on information provided by X and Y according to the specifications and assist them in registering their own individual sites at different domain names.

This solution provides a mechanism to honor concurrent trademark user rights. Principally, it gives the trademark owners what they may desire, which is a presence on the web at the domain name corresponding to their trademark. The linking page is randomized so that it does not discriminate against one owner over another. It also provides, through the arbitration clause, an efficient manner to resolve disputes. The rights in both registered and common law marks are recognized, and the linking page is controlled by the organization in the best position to know of the overlapping domain requests. End users also benefit from the solution because it provides more information to them so that they can differentiate between concurrent trademark users. It provides for better guessability, allowing the end user to intuitively determine a business' domain name.

One possible weakness of the proposal would be the ownership of the linking pages. Although top-level domain registrars may argue that the linking pages would place an additional burden on them, it would appear that maintenance of the sites would be minimal and once the system is in place would take little effort. The registrars are the optimal entity to have ownership of the sites, as they control registration of the domains and would be able to monitor when two businesses request the same domain name. Overall, this solution would provide the most benefit to all the parties involved.

The competition for domain names is guaranteed to increase as more businesses desire to create a presence on the web. Concurrent trademark use presents a unique problem for this development. Proposed solutions to the problem when two or more concurrent trademark users both wish to use their trademark as a domain name fail to take trademark owner and end user considerations fully into account.

This paper's proposed solution involving the creation of a linking page would provide benefits for both trademark owners and end users and create minimal burdens. Trademark owners would obtain a presence on the web at the domain name which corresponds to their trademark. End users would be able to intuitively guess the domain name for business sites on the web, and confusion on whose goods or services are represented on a web site would be minimized. This solution would provide a novel answer to a novel problem which neither current trademark law nor domain name policy is prepared to resolve.

NOTES

[1] James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 11 (1996). [2] See Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) (1998). [3] Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1)(a) (1998). [4] Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) (1998). [5] David B. Nash, Comment, Orderly Expansion of the International Top-Level Domains: Concurrent Trademark Users Need a Way Out of the Internet Trademark Quagmire, 15 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info. L. 521, 531 n. 93 (1997). [6] The domain name www.acme.com is used throughout the paper as an example. The domain is actually owned by ACME Laboratories. See Jef Poskanzer, ACME Laboratories, (visited Mar. 23, 1999) <http://www.acme.com>. [7] IP numbers are assigned by the IANA. See Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, IANA Home Page, (last modified Mar. 10, 1999) <http://www.iana.org>. [8] Matisse Enzer, Glossary of Internet Terms, (last modified Mar. 7, 1999) <http://www.matisse.net/files/glossary.html>. Other protocols used on the Internet include the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) and the Network News Transport Protocol (NNTP). [9] See Network Solutions, Frequently Asked Questions Registration-related terms, (last modified Nov. 01, 1998) <http://www.internic.net/faq/glossary.html>. [10] Network Solutions, Domain Name Registration by Network Solutions, (visited Mar. 10, 1999) <http://www.networksolutions.org>. [11] See Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, IANA Home Page, (last modified Mar. 10, 1999) <http://www.iana.org>. [12] See Network Solutions, Welcome to the InterNIC, (visited Mar. 10, 1999) <http://www.internic.net>. [13] See Network Solutions, Domain Name Registration by Network Solutions, (visited Mar. 10, 1999) <http://www.networksolutions.org>. [14] David J. Loundy, Domain Name Symposium: A Primer on Trademark Law and Internet Addresses, 15 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info. L. 465, 470 (1997). [15] Id. [16] Id. at 466. [17] James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 11 (1996). [18] See Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) (1998) [19] In these cases, the telephone companies normally provide the numbers on a first-come, first-served basis, meaning that the first business to register the vanity number is the winner and the second business has to live with a less advantageous alternative. James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 12 (1996) ("Like NSI, telephone companies assign numbers on first-come, first-served basis, making the courts sort out the trademark issues."). [20] See e.g. Hasbro, Inc. v. Internet Entertainment Group, Ltd., No. C96-130WD, 1996 U.S. Dist LEXIS 11626 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 9, 1996); Comp Examiner Agency v. Juris, Inc., no. 96-0213WMB, 1996 WL 376600 (C.D. Cal 1996). [21] Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) (1998). [22] See e.g. Panavision Int'l L.P. v. Toeppen, 938 F. Supp 616 (C.D. Cal. 1996); Intermatic, Inc. v. Toeppen, 947 F. Supp 1227 (N.D. Ill. 1996). [23] Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1114 (1998). [24] David Peter, Frenchy Fries™ homepage v5.01 (last modified Feb. 17, 1998) <http://home1.gte.net/dpeter1>. [25] Fry's Electronics, Inc. also operates the other registered domains of www.fryselectronics.com and www.fry-s.com. [26] Richard Zaitlen and David Victor, The New Internet Domain Name Guidelines: Still Winner-Take-All, 13 NO. 5 Computer Law. 12, 16 (1996). [27] Fry's Electronics v. Octave Systems, Inc. et al., First Amend. Complaint, Case No. C95-2525-CAL (N.D. Cal., Jul. 13, 1995). [28] Call it trouble.com, USA Today, News Section, Pg. 10A (January 15, 1997). [29] See Network Solutions, Network Solutions' Domain Name Policy (last modified Feb. 25, 1998) <http://rs.internic.net/domain-info/internic-domain-6.html>. [30] Network Solutions, Network Solutions' Domain Name Policy (last modified Feb. 25, 1998) <http://rs.internic.net/domain-info/internic-domain-6.html>. [31] Richard Zaitlen and David Victor, The New Internet Domain Name Guidelines: Still Winner-Take-All, 13 NO. 5 Computer Law. 12, 15 n.27 (1996) (quoting NSI Domain Dispute Resolution Policy Statement of July 7, 1995). [32] Network Solutions, Frequently Asked Questions Network Solutions' Domain Name Dispute Policy (Rev. 03) (last modified Sept. 23, 1998) <http://rs.internic.net/faq/dispute.html>. [33] Network Solutions, Network Solutions' Domain Name Policy §§ 8-9 (last modified Feb. 25, 1998) <http://rs.internic.net/domain-info/internic-domain-6.html>. [34] See Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125 (1998). [35] Catherine Simmons-Gill, Copyright Protection on the Internet: Statement of the International Trademark Association Before the Subcomm. On Courts and Intellectual Property of the House Comm. On the Judiciary on H.R. 2441 104th Cong., 1996 WL 50058 (1996). [36] See D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [37] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [38] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [39] Catherine Simmons-Gill, Copyright Protection on the Internet: Statement of the International Trademark Association Before the Subcomm. On Courts and Intellectual Property of the House Comm. On the Judiciary on H.R. 2441 104th Cong., 1996 WL 50058 (1996). [40] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [41] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [42] David B. Nash, Comment, Orderly Expansion of the International Top-Level Domains: Concurrent Trademark Users Need a Way Out of the Internet Trademark Quagmire, 15 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info.L. 521, 538 n.176 (1997). [43] See Internet International Ad Hoc Committee, IAHC Home (last modified May 26, 1997) <http://www.iahc.org>. [44] International Trademark Association, V. Domain Name System Models: Current and Proposed (last modified Nov. 20, 1997) <http://plaza.interport.net/inta/wpii.htm>. [45] James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 12 n.48 (1996). [46] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [47] E.g. Ms. Sharp's personal web page at www.sharp.personal.com could be distinguished from Sharp Electronic's business page at www.sharp.com. See James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 12 (1996). [48] James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 12 (1996). [49] Id. [50] See e.g. International Trademark Association, V. Domain Name System Models: Current and Proposed (last modified Nov. 20, 1997) <http://plaza.interport.net/inta/wpii.htm> (proposing to add .FIRM, .SHOP, .WEB, .ARTS, .REC, .INFO, and .NOM as new top-level domains). (See also the Postel Plan, proposing to create up to 150 new international top-level domains). [51] D. Collier-Brown, On Experimental Top Level Domains Rev 0 (Sep. 1996) <http://java.science.yorku.ca/~davecb/tld/experiment.html>. [52] Federal Communications Commission, Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Home Page (last modified Apr. 2, 1999) <http://www.fcc.gov>. [53] David B. Nash, Comment, Orderly Expansion of the International Top-Level Domains: Concurrent Trademark Users Need a Way Out of the Internet Trademark Quagmire, 15 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info.L. 521, 543 (1997). [54] See AlterNIC, AlterNIC.NET Network Information Center (visited Feb. 28, 1999) <http://www.alternic.com>. [55] See New Domains, Welcome to New Domains (visited Feb. 28, 1999) <http://www.newdomains.net/default.htm>. [56] International Trademark Association, V. Domain Name System Models: Current and Proposed (last modified Nov. 20, 1997) <http://plaza.interport.net/inta/wpvcd.htm>. [57] James W. Morando and Christian H. Nadan, Can Trademark Law Regulate the Race to Claim Internet Domain Names?, 13 NO. 2 Computer Law. 10, 12 n.48 (1996) (citing the INTA Bulletin, December 28, 1995 at 10).