Wendell Johnson, A Son’s Perspective

(Note: For more information about books mentioned in this webpage, go to the “Wendell Johnson Memorial Web Site Index and Contents”/“Books” section.)

My father — known to me as “Dad,” to his students as “Dr. Wendell Johnson,” and to his close friends as “Jack” — was my best friend.

This website has been created as a memorial to him, and a source for the curious as well as today’s students and practitioners of communication sciences and disorders, including speech pathology — and general semantics.

This page contains some of his son’s comments about his father.

I believe a website is an appropriate medium for his memorial. Before his death Dad wrote of his electronics hobby — at that time the work he was doing with audio tape recorders, including the invention of a rather ingenious dual-deck machine to enable individuals to hear, and react to, their own speech. I am confident that, had he been alive in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he would have been among the first to explore a PC, the Internet and today’s Artificial Intelligence.

Born in Roxbury, Kansas, in 1906, he arrived in Iowa City in 1926, earned a B.A. with honors in English in 1928, and two degrees in psychology: an M.A. in 1929 and Ph.D. in 1931. He spent much of his life attempting to create the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology, which only occurred after his death and is now called the “Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders.”

He died of a heart attack at his home in Iowa City, Iowa, August 29, 1965. He was then 59. A writer, he literally died with a pen in his hand, drafting the entry on “Speech Defects” for the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Dad began life as a stutterer. As he put it, he became a speech pathologist because he needed one. At the University of Iowa in the 1920s and 1930s he may have been one of the first ever stutterers to promote academic research and study of stuttering.

When my father died in 1965 the family received literally thousands of moving letters of condolence and anecdote from around the world. He had touched so many lives in his brief 59 years, and in ways that often left those he encountered full of admiration, appreciation and affection they never forgot.

That fact is relevant to this Web site. (1) It is because he was that kind of a person that I believe it worth my time — and yours — to be reminded of him through the material available through this Wendell Johnson website. (2) There are still some individuals who knew him personally, or by way of others’ stories. It may be more pleasant than sad for them to visit again in this way with their old friend “Jack.” (3) The new waves of students, teachers and practitioners of speech pathology — and of general semantics — may find this website’s links a useful way to satisfy some curiosity about this early pioneer in their specialties of study, research and practice.

It would be an odd science indeed if all of his 20th Century insights and theories were still thought valid today; but they will always be prominent in understanding the origins of these fields.

There would be little point in this website providing links to the full text of everything Dad wrote. There were literally hundreds of books, articles, monographs and book reviews — not to mention all the master’s theses and doctoral dissertations he supervised. But this website includes bibliographies of them, and a sampling of some of his works.

Moreover, this website does contain the full text of one of his books: his first.

Wendell Johnson’s master’s thesis was published commercially by D. Appleton in 1930. That fact alone represents no mean accomplishment!

The book has, of course, long been out of print. Copies have been lost from some libraries, thereby leaving this website as one of the few sources for the book. The text has been scanned and is available here in full, subject to the copyright terms explained within the text.

The book is titled Because I Stutter. Even discounting for the fact he was my father, I think you will share my sense that it is a remarkable work for a 23-year-old: beautifully written, unusually candid and insightful, a self-revealing illustration of how one’s origins affect destinations, description of life in 1910s and 1920s America, and a speech pathology classic — one of the first works of any kind about “stuttering,” and still one of the very rare descriptions of stuttering from the perspective of a person who stutters.

As remarkable as Because I Stutter may be for what it is, it does not purport to be, and could not be, based on any of the research findings from the 35 years following its publication. Two volumes that do are Stuttering in Children and Adults (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955), and The Onset of Stuttering: Research Findings and Implications (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1959). There are many other books which he wrote, co-authored, or edited. There are also hundreds of articles and monographs. Stuttering in Children and Adults contains “A Bibliography of University of Iowa Studies of Stuttering through 1954” that runs 17 pages of very small type.

Drawing upon these two volumes, he produced a third, Stuttering and What You Can Do About It (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1961), written to reach a larger audience. (It was also published in paperback: Stuttering and What You Can Do About It (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1961), as a “Dolphin Handbook,” C-349, and in Japanese and Turkish language editions. Adil Uskudarli, who prepared the first Turkish translation, completed a second edition in late 1999.)

Just as Because I Stutter provides insights into all youth, especially those with disabilities of some kind, and not just stutterers, so does Stuttering and What You Can Do About It offer far more than a “how to” cure for stuttering. It is a mystery story, a case study of how Dad, and his colleagues at Iowa, went about designing and executing scientific research regarding a phenomenon about which virtually nothing was known. There was no “library research” to be done; no teachers, consultants, or experts to help.

The story of what they did, when, why, and then what, can provide insight for others confronting comparably original research assignments. How they formulated, and then answered, the questions is a mystery story unfolding. (Of course, the book also provides some useful guidance and insight for parents and stutterers.)

General Semantics and People in Quandaries

In addition to his contributions as a speech pathologist, Dad was a leading figure in the general semantics movement. (The online Encyclopedia Britannica entry for “General Semantics” once read that it is “a philosophy of language-meaning that was developed by Alfred Korzybski (1879-1950), a Polish-American scholar, and furthered by S.I. Hayakawa, Wendell Johnson, and others; it is the study of language as a representation of reality.”)

Indeed, if you are already familiar with Dad’s writing you know that the insights and analyses made possible with general semantics were central to his analyses of the onset of stuttering and other speech defects, as well as disabilities generally.

To grossly oversimplify, general semantics is the study of the ways in which our language structure can affect our behavior — and often not for the better. As Dad used to say, “Humans are the only animals able to talk themselves into difficulties that would not otherwise exist.” As a result, general semantics is a valuable set of tools and skills to bring to any undertaking, from managing a drug store to engaging in the highest levels of international diplomacy. It has been used to advantage by professionals in virtually every academic and professional discipline.

As a young boy I found in these tools a power of heady proportions in interacting with our learned, adult house guests. You may find of interest a nostalgic piece of mine about growing up in the home of one of the founders of general semantics. It was presented as the 1995 Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture for the Institute of General Semantics, https://www.nicholasjohnson.org/rcntpubl/korzyb.html .

The book of Dad’s that probably garnered the most devoted adherents, sold the most copies, and stayed in print the longest is People in Quandaries: The Semantics of Personal Adjustment, published by Harper & Brothers in 1946. (Some chapters are reproduced in Nicholas Johnson’s book, What Do You Mean and How Do You Know: An Antidote for the Language That Does Our Thinking for Us (2009; Lulu; 185 pp.) https://www.amazon.com/What-You-Mean-How-Know/dp/055707925X/ ).

One of general semantics’ most popular areas of application is the field of psychology. Dad describes what he calls the “IFD” disease as one of the most common maladies he encountered as a consulting psychologist. It’s a chapter I have often shared with friends. He titled it “Verbal Cocoons,” https://www.nicholasjohnson.org/wjohnson/wjpinq.html .

However, the book that he most enjoyed creating, and thought perhaps his best writing, was titled Your Most Enchanted Listener (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956). (It was also published in paperback under the title Verbal Man: The Enchantment of Words (New York: Collier Books, 1965, No. 04669.) The excerpts here are chapter 1 (“There Might Once Have Been a Wise Old Frenchman”) and chapter 7 (“Seeing What Stares Us in the Face”). The former is a charming introduction; the latter a succinct statement of his view of a scientific method that can be applied to everyday life. https://www.nicholasjohnson.org/wjohnson/wjymel.html .

Following his death, his colleague, Dorothy Moeller, produced from his unpublished writing and lectures a marvelous little book entitled Living With Change: The Semantics of Coping (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), also in paperback. (She described the authors as “Observations by Wendell Johnson Selected and Synthesized by Dorothy Moeller.”) In an age when business, and other literature, is emphasizing the need to observe, innovate, and deal with rapid change in creative ways, Living With Change seems especially timely. Here is an excerpt from Living With Change, https://www.nicholasjohnson.org/wjohnson/wjlwc.html .

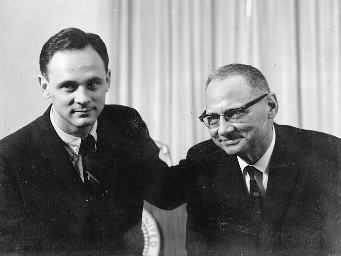

Dad and I in the Cabinet Room at the White House. We are standing before a podium with the Presidential seal. It is March 1, 1964, and President Lyndon B. Johnson is having me sworn in as the U.S. Maritime Administrator. All my life to that point I had often been referred to as “Wendell Johnson’s son” — and proud to be. On this occasion, a reporter approached Dad and said, “You must be Nicholas Johnson’s father.” Dad often told the story and, as you can see, was seemingly even more pleased with the occasion — and his new title — than was the new, 29-year-old Maritime Administrator.

# # #